Three thousand words about not writing.

I'm not writing a novel, and I'd like to tell you about it, and you get to hear my inner critic as we go.

Are you kidding? 3000 words?

Don’t worry, I’m not crazy. I’m not going to throw 3000 words at you at once. This is a two-part issue here. You get the first half this morning, and the second half next week.

But, why aren’t you writing about drawing? Everyone is only really here for the cute pictures, you know.

I promise, I’ll include cute pictures.

Okay fine, for now. But I might unsubscribe if this isn’t good.

Fair enough. Don’t forget to read the footnotes.

Once upon a time…

One of the reason I began writing a newsletter was so that I might start actually, you know, writing. Seems obvious, doesn’t it? Well, it’s not. Drawing comes easily to me. I draw and I sketch all the time. I can draw with a broken pencil, and I can draw with a ballpoint pen, or with an iPad, or even a stick dipped in ink. I can draw in my studio where I’m supposed to draw, but also in the car, on the bus, on vacation, around people, with music on… it really doesn’t matter. However, if you give me any excuse to not write — the wrong sort or paper, I’m busy, too distracted — I’ll just not do it. And this is a problem.

It’s a problem because the projects that are the most important to me are projects that I need to write, and I’ve not been writing them. Right now, three of these are picture books: one about an insect (which is in fact more or less written, but it doesn’t feel right yet), one is a rhyming book about a duck and a truck (in which I have “duck” and “truck” written, so I’m two words in at least), and the third is another possibly-rhyming story about a brother and a sister having some sort of squabble (which has even less written than the duck/truck book, because rhyming books about sibling squabbles are hard to write. Though they’re really fun to draw.)

And while each of these projects is proving difficult for whatever reason, they’re really small potatoes compared to the “novel” that I’ve been “writing” since around 2019.

Picture books ≠ novels, and vice versa.

Before I get too far with this, I need to mention that I’m not going to fall into the trap of comparing writing a novel to writing a picture book. It’s a problematic comparison and one that gets children’s book people like myself just a little bit defensive. We hear all the time about how easy it must be to make a book that’s just 32 pages. Okay, fella, you think writing a good and meaningful story in 32 pages with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and a conflict, and character development, and resolution in 350 words is easy?1 Ha ha, okay go do that. Then let’s talk.

The difference, at least for me, is that I can wrap my brain around a picture book. I can “see” the beginning, the middle, and the end as I’m beginning the process of writing. I suspect this is because a picture book is inherently a visual medium, full of drawings, and, as I mentioned, that part comes easily to me. Almost all of the picture books I’ve written began with pictures.2 I guess I think of a picture book as a stage where I can place characters, and a story structure, and sequences of illustrations, and it all sort of makes sense. In almost every case the words came after I was well into the process. I wouldn’t say they’re an afterthought, no more than with a band who lays down melody before the lyricist adds words.3 The words carry their own weight and the story doesn’t work without them.4 It’s just that I usually visualize a story first with some amazing image in my head, and then I use words to connect those pictures.5

You guys are amazing!

Let me take a moment here to wax with admiration about the writers of picture books who don’t illustrate. I’m thinking of you, Kelly DiPucchio, and you Mac Barnett, and you Cynthia Rylant, and the dozen or so other writers I’ve collaborated with on picture books. I just don’t know how this is done. How does someone write a story for a picture book without leaning hard into “this will go here and that character will be doing this and then the page turn and then that happens, etc” as they go? I don’t get it and I think it’s something mysterious and magical. When I get a new manuscript to illustrate, the first thing I do is read it several times to locate the rhythms and various signposts inherent in the story. By the fourth or fifth read, I’ve started marking page-turns and taking count. And you would not believe how often it’s worked out that when this is done, it just naturally lands on 32, or 40 pages. How do you do that?

But as I was saying…

So, novels. I really believe that novels aren’t objectively harder. They’re different. Longer, sure. But longer isn’t the problem. It’s more like, a novel to me is hidden. It’s behind those trees over there and underneath that rock. I can’t really see it but I know it’s there. This is probably because it’s not really visual. Mine will have illustrations. Lots of them, in fact. But they won’t be driving things. And, again, writing words doesn’t come as easily for me. I have to do a lot of work before i can get a grasp on what this book is.

Or, what it isn’t. That’s part of this. I’ve had false starts and i’ve gone down the wrong roads with my picture books, and changing course doesn’t feel like a giant scary problem because of the inherent constraints of a picture book. When something goes off the rails, I can still see to the other side. But with this novel, I’m almost afraid to write anything, to put anything on paper (or word processor), for fear that it isn’t the right thing. Because it could be anything. I know the ins and outs of writing a story, and I know that inspiration doesn’t just happen. There’s that inspiration and perspiration quote,6 and my belief that making art is a discipline, a real job. So bear with me as I’m working all this out, right here in front of you.7

Something funny, or maybe ironic, about this novel I’m writing, is that it began as a picture book! Twenty years ago (!) I had this idea for a funny story about a group of neighborhood boys who all get new bikes for Christmas. There is a girl on the block, who happens to be an alien, let’s call her Frida, and she gets a flying saucer. All the boys are jealous. The whole idea revolved around this one image in my head, a birds-eye-view of a group of boys surrounded by their bikes, all looking up at Frida in her flying saucer. The boys are all crazy-jealous, all except one, who is madly in love. And it was called Frida Had a Flying Saucer. So perfect! So simple.

But then it wasn’t, and it got put on hold. I don’t remember why it wasn’t working. Probably because I’d never actually written a picture book at that time, and it read like a story written by someone who didn’t know what he was doing. “And then this happened, and then that happened, and then…” You know what i mean. Like the story your neighbor wrote about her dog that she wants you to illustrate for her so she can get it published.8

The plot thickens!

Most of us in the writing-books business have a pocket full of book ideas that we can pull from and read aloud at any given moment. You never know when you might run into an editor from HarperCollins on a train or elevator. Or a bookstore owner might ask you what you’re working on next and you’d better have something good. So, when we have an idea, we put it in that pocket and let it marinate and simmer (you like mixing metaphors? I do!) with all of the other ideas. Fast forward to 2017, I’m in Santa Cruz, California, on the tail-end of a book tour with a well-known author. One evening we’re talking books at the hotel bar, and I pull this Frida Flying Saucer thing out of my pocket, and I mention to him that I’m stuck, see, and I have no idea what to do with this picture book story about a boy with a bike who has a crush on the alien neighbor girl with the flying saucer. And this genius, this well-known author says “well that’s not a picture book.”

“It’s not?”

“No. Six year olds in picture books or reading picture books don’t have crushes. They don’t care about that sort of thing.”

And he was right.

I stewed on this for a few weeks, and a little later i was talking to my good friend Amy who is an author/illustrator (as opposed to an illustrator/author like me) and who knows a thing or two, and she says “what you have here, Brian, is a middle-grade novel.”

“A middle-grade novel?”

“That’s right, a middle-grade novel,” Amy said. “And the great thing about that, is that in a middle-grade novel, anything can happen. Anything. See, there are rules in picture books. You know, you can’t do this and that because the readers are so young. And you can’t do this or that in Y.A. either because the readers are teenagers and all angsty and so serious. But in middle-grade, by golly, anything can happen. If you have some kid with a crush on a girl from outer space, or an alien dog, or a house that just flies away, that makes total sense in a middle-grade novel.”9

This got me excited. I’m going to write a middle-grade novel! I cleared the desk, I sharpened my pencil, I opened a new Word document, and then…

Really? A cliffhanger?

To be continued next week!

Where the Wild Things Are, for example, has only 336 words, but it does more with those 336 words than most novels do with 75,000. Writing a picture book is like poetry.

If there is an exception, it’s probably the 2nd Tinyville Town picture book, Time for School. This is the one time I knew what I wanted to do totally within a story, and while there were one or two places where the structure of the Tinyville Town books dictated this story, the pictures all came later.

Read David Byrne’s How Music Works for more about this. I think R.E.M. wrote this way as well.

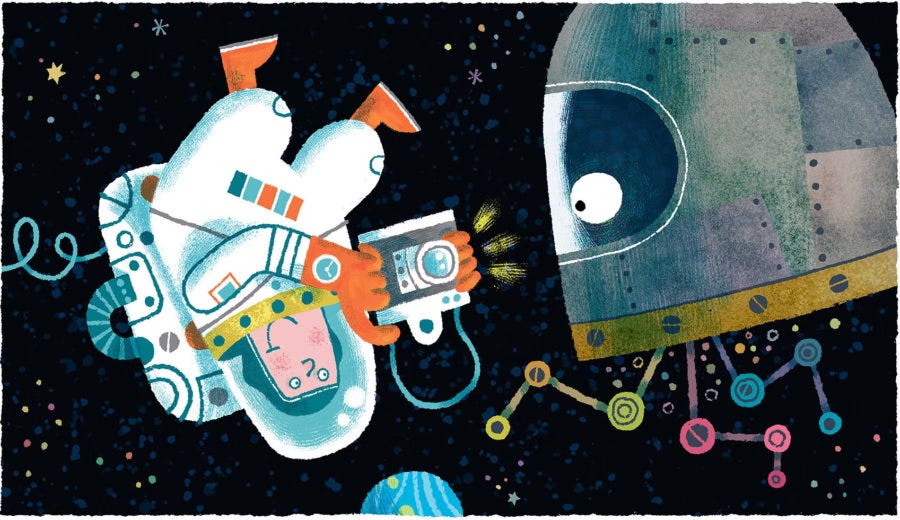

I’ve attempted to write wordless picture books. The Space Walk was wordless in some of its earliest iterations. And a section of it, the part set outside the space capsule, is silent in the finished book. Because in space no one can hear you scream. Or laugh and snap selfies as the case may be.

Maybe this is a problem with my writing, with my books. I don’t know. I think about it a lot.

“Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.” - Thomas Edison

Let’s be honest here, though. I could be completely wrong about all of this. Maybe they are harder. I don’t know, I’ve never actually written one. That’s my point.

I realize that not all of my readers here are fellow children’s book illustrators and get pitched ideas by neighbors, but c’mon. I bet you know exactly what I’m talking about.

I don’t think Amy mentioned a girl from outer space or an alien dog or a flying house, specifically, but it was something like that, and since my story actually has these things, I’m using them here.

This. So much. I have been trying to remind myself that I can't be a writer - an author/illustrator, that is - if I'm not writing (and drawing). It sounds so obvious, but for whatever reason, I have to keep reminding myself. More verbing to become the noun.

I love it that you finally figured out your writer's block was because you were writing to the wrong age group. Now that you have middle schoolers in mind, where anything can happen, who knows? Maybe it will just fall out of the sky. Hopefully not on the boys, especially the one with a crush on Frida. It reminds me of a story my son and I were playing with when he was in middle school. Now he is 43. So the details are a little fuzzy at the moment. I should ask him if he remembers it.